Language and poetry: if there's a way to separate them, I don't know it. But despite the heartbeat meter underlying most lyric poetry, and the sensuous slide of alliteration and rhyme plaiting the lines together, and the laid-in pauses and rhythms of the page, the line, the spacing -- well, despite the way one hear's a poem as one reads it, MI REVALUESHANARY FREN demands a different kind of reading. A reading aloud.

Intrigued by the unexpected gift of an introduction by novelist Russell Banks (the book's published by his wife Chase Twichell's Ausable Press), I pressed into reading this September 2006 release. Poems like "All Wi Doin Is Defendin" seemed straightforward enough, but hard on eye-brain linkage as I sounded out the Jamaican Creole on the page:

war ... war ...

mi seh lissen

oppressin man

hear what I say if yu can

wi have

a grievous blow fi blow

wi will fite you in di street wid we han

wi hav a plan

soh lissen man

get ready fi take some blows

And so it goes on, line after line, stretching the inner eye-ear to make sense of the page, with the finale:

all wi doin

in defendin

soh set yu ready

fi war ... war ...

freedom is a very fine thing

AH! Revolution to achieve freedom -- it's an American virtue, and from war in the streets, I translate at the final stanza to why so many of us react so strongly to, say, the Rodney King beating, hate crimes against gays, the double binds of victims of domestic violence (need I mention OJ's family?), desperation on Native American lands, laws that punish immigrants for having roots elsewhere.

But to be American and middle class and white is a hard place to be when identifying across color lines. Even to fully recognize what generations of enslavement-via-skin-color did to our nation's ideals and humans take hard work for those living the presumed easy life.

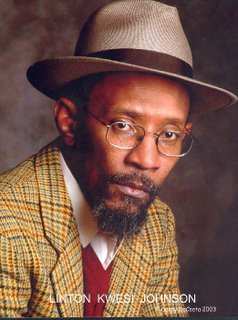

Linton Kwesi Johnson, better known as LKJ, born 1952 in a small town in rural Jamaica, arrived in London in 1963, for secondary school and later studies in sociology at Goldsmiths' College, University of London. Here he joined the British Black Panthers and helped organize a poetry workshop within the movement. His published poems and his music erupted together through the 1970s, bringing him recognition that came by definition internationally: You can't separate him from either England or Jamaica. By the 1980s he'd entered radio journalism. The awards piled up momentously: associate fellow of Warwick University (1985), honorary fellow of Wolverhamption Polytechnic (1987),an award from the city of Pisa (Italy) for his contribution to poetry and music.

Under the conventional list of awards and achievements (his own record label; "the second living and the first black poet to have his selected poems published in England in the Penguin Classics series" -- says Banks in the introduction) is a concentrated focus on oppression and resistance. People are killed regularly within the "revolutions" that demand freedom and rights.

there are sufferers with guns movin breeze through the trees

there are people waging war in the heat and hunger of the streets.

("Song of Blood")

I'm seized by "sufferers with guns, and by "heat and hunger." This isn't revolution as an intellectual excercise; it's revolution as survival. As necessity. As breath, and as chilbirth. I remember what I did to make sure my kids were fed (stomach, heart, mind); I would do it again. LKJ's lyrics remind me of how some things just have to be done, no questions, no "I can't" -- you move, you go to the front lines.

Poems here that stay with me include "Inglan Is a Bitch" (opening with work, as an immigrant, in the Underground/subway), "Reggae Fi Radni" (in memory of hate crime victim Walter Rodney), "New Crass Massakah" (about the racially motivated arson in 1981 that killed 14 young blacks at a 16th birthday party, 1981), and in the Nineties Verse that makes up the final section of the book, "If I Woz a Tap-Natch Poet" and, especially, "Hurrican Blues," which opens:

langtime lovah

mi mine run pa yu all di while

an mi menbah how fus time

di two a wi com een--it did seem

like two shallow likkle snakin stream

mawchin mapless hapless a galang

tru di ruggid lanscape a di awt sang

But it wasn't until I captured my husband at a moment when he could listen, and began reading awkwardly aloud to him, that I felt, heard, saw the drums and pounding feet and bass guitar and breathing in and under the words.

When the students at Kent State were attacked, there were new openings in the revolution, for white middle-class college kids like me. When the revelations of My Lai and Abu Ghraib unfolded, there were more places. When I hear a small child in my beloved Vermont landscape say, uncorrected, to her father, "Chinese people say chinky-chinky-chong," the revolution calls again.

And on every page of MI REVALUESHANARY FREN, there is another clang of the bell.