For Chase Twichell, long-time publisher of Ausable and now an editor at Copper Canyon, the publication of DOG LANGUAGE in 2005 plumbed not the woofs and barks of her four-legged companions, but more the sense of herself as she ran with them or considered them from the poignant distance of friendship across species. In the opening poem, "Skeleton," her dogs dig in the snow for relics of what once was -- and the poem expands in a final stanza:

I asked Truth what to worship,Ah! Not only are we translating each other's languages, but the poet can become the voice of the skull. Twichell follows up on this promise with "Sorry" as she details the sensations of using both hands to break the skeleton of a trout; and with "Auld Lang Syne," when the grown-ups at the gathering rise from their cocktail-blurred selves to remove porcupine quills from a dog:

and Truth said Death,

looking up from licking

the caviar of moments

from Death's hand.

So here are the bones

in the exploded view,

pelvis and vertebrae,

thrown dice of hands.

Look at the skull.

I'm its voice.

They use pliers, and afterwardTwichell explores childhood and drug use and especially the distance a child is from a parent, naming the hesitant touch "animal caution" as she reaches toward stones "marking the summit of one of my parents." I like particularly the poem "Dog Biscuits" that tongues the gap in the inner teeth left by the loss of a father to death, ending:

the dog wags in apology

and the drinking resumes.

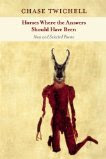

It'll be just us, the three inheritors,This year, a new collection from Twichell gathers selections from this and four other earlier collections, in HORSES WHERE THE ANSWERS SHOULD HAVE BEEN (Copper Canyon, 2010). These poems reach back to 1981, well before her marriage to novelist Russell Banks. And they extend to fresh animal forms: horse, mule, pony, centaur. From "The Long Bony Faces of the Mules":

on a raw windy day in Death's kingdom,

lifting our eyes from the hole

to the mountains hazed with sping,

saying, In perpetuum ave atque vale,

minor god of our father.

Let's each of us drop a few

dog biscuits into his grave.

I knew nothing of the fences words makeTwichell tongues her Zen Buddhist practice in the final poems, sampling silence while speaking, so to speak. She tests the nature of meditation, concluding, "I must not want to be fully enlightened, / since I do not devote myself entirely to it. / I like distraction."

in the mind, or that I would devote

the first half of my life to building them

and the second half to tearing them down.

And at last she takes us back to her animal languages, as she writes in "From a Distance,"

Of all the selves I've invented,And with the gentle sombre probing that is more and more present in her work, she wraps up this poem with: "Death will come / and take me to them, and a new self will begin / to ask these questions as if for the first time."

the ones most fixed in memory

are the horse-child startling

the dog-child sniffing the still-warm ashes

where the smell of food has almost been erased.

If this is what the second half of Twichell's poetry will continue to bring to us, as it "tears down" the fences of words, then another answered question becomes: What can the second half of life bring, besides the inevitable loss of aging pets, loss of friends, loss of parents? And the answer is: Grace.

No comments:

Post a Comment